- Home

- EDDIE RUSSELL

THE MADNESS LOCKER

THE MADNESS LOCKER Read online

THE

MADNESS

LOCKER

Copyright © Eddie Russell

First published 2021

Copyright remains the property of the authors and apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission.

All inquiries should be made to the publishers.

Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 303, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia

Phone: 1300 364 611

Fax: (61 2) 9918 2396

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.bigskypublishing.com.au

Cover design and typesetting: Think Productions

Printed in China

For Cataloguing-in-Publication entry see National Library of Australia.

THE

MADNESS

LOCKER

EDDIE RUSSELL

Inspired by true events.

CONTENTS

Winter 1941

Bellevue Hill, Eastern Suburbs, Sydney: Autumn 1986

Universität Leipzig: Autumn 1934

Bellevue Hill, Eastern Suburbs, Sydney: Autumn 1986

Rackelsweg, Bremen: Autumn 1934

Utrecht: Autumn 1934

Grünewald S-Bahn Station, Berlin: Winter 1942

Deportation, Berlin: Winter 1942

Berlin: Spring 1943

Bellevue Hill, Eastern Suburbs, Sydney: Autumn 1986

Berlin: Summer 1943

Bremen: Autumn 1944

Bellevue Hill, Eastern Suburbs, Sydney: Winter 1986

Utrecht: Winter 1944

Berlin: Winter 1944

Utrecht: Winter 1944

Berlin: Winter 1944

Mascot, Sydney: Winter 1986

Auschwitz: Winter 1944

Utrecht: Winter 1944

Surrender: May 1945

Berlin: Autumn and Winter 1945

Bellevue Hill, Eastern Suburbs, Sydney: Winter 1986

Bellevue Hill, Eastern Suburbs, Sydney: Winter 1986

Berlin: Winter 1945

About the Author

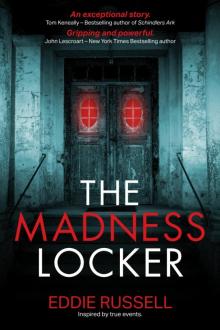

PRAISE FOR THE MADNESS LOCKER

'Gripping and powerful. The Madness Locker is not

merely a great debut novel. It is a great novel period!’

John Lescroart - New York Times Bestselling author

‘An exceptional and teasing story about history,

contingency, the dignity of humans and fragility of our hold

on the earth. You will not easily forget these women.'

Tom Keneally - Bestselling author of Schindler's Ark

INSPIRED BY A TRUE CRIME

On Christmas Day, 1986 an elderly widow’s body was discovered inside a wheelie bin in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney, Australia. Despite a long and intensive investigation, the police fail to unearth a motive or identify a suspect. Lacking any clues, the police file it as a cold case. This fictional story, inspired by the true event of her murder, proposes a plausible motive.

WINTER 1941

I would have died when I was ten. But I didn’t, and you would think that that was my good fortune. Except other people that I hold dear died and another paid dearly in my stead for that stroke of luck. And, well, it is a strange and bewildering memory to behold, but back then, as I think of it, and I do think of it often, the shards of a shattered past that reflect on my life today are a constant reminder of how an orderly, ordinary life unravelled violently. It did so with such ferocity, and that may be the salve that quiets my troubled conscience; that no one, least of all me, had time to prepare or plan. The irony is that had my life not imploded I would not be here and the events that unfolded would have never happened.

It started well before I was even born. I was ten when I became keenly aware of the troubles. That’s how I often heard my parents, Heinrich and Alana Lipschutz, refer to the upheavals in Germany. I would be in bed, listening intently, late at night, to their hushed conversation in the dining alcove that was adjacent to my room. I could tell that they were upset and worried. But most of what they said I didn’t understand. They talked about evacuation, deportation, Palestine, Nationalsozialisten, Hitler.

On one particular occasion other couples came by, without their children, which I thought odd, and they all huddled around the dining-room table, drinking tea or wine, and the same words came up. Except a word that I had not heard before had them all in a state of panic: Kristallnacht.

I am Ruth. And it took a little while longer for the troubles to trouble me. I had just turned ten when I was called into the school principal’s office. Herr Baumgartner, a dour man with a permanent frown, asked me to sit down as soon as I came in. My parents were there too, seated with their backs to the door. As soon as I saw them I knew I was in trouble. My heart sank, and in a state of panic I thought back to every little misdeed that I had committed to prepare a defence for what might have come to light.

“Mr and Mrs Lipschutz,” Herr Baumgartner began in a hoarse voice, “Ruth is a wonderful pupil: well behaved, excellent marks, impeccable attendance. And for our part this school has tried to keep our pupils protected from all the troubles that are going on out there. As such I have been avoiding this. But...” Here he faltered and placed a piece of paper on the desk, right side up, facing my parents.

My father reached across and took the piece of paper and held it between him and my mother. They both read silently. I could see Father’s face turn grave, like when he learned that Grandpapa had died, and Mother started sobbing.

“I am now forced to comply or I will be fired from this post and put in jail. Or even worse,” Herr Baumgartner resumed, seeing my mother’s distress.

My father was overcome with sadness and didn’t say anything. He just nodded and reached for my mother’s hand. Silently they stood up and both shook Herr Baumgartner’s hand, taking the paper with them. For the only time I can remember, Herr Baumgartner displayed a smattering of emotion. His hand quivered and, in a voice edged with pain, he said, “I am very sorry. I will go and collect Ruth’s things from the classroom. If you can just wait in the outer office.”

My parents did not speak until we got home. We each carried some of my school belongings: books, notebooks, drawings, old assignments, stationery and even a commendation that I had received from one of the teachers. A sad parade of departure from what had hitherto been my daily life.

At home, Father didn’t say anything other than that he had to go back to the shop. Mother made me a lunch of a marmalade sandwich, milk and chocolate biscuits: my favourite. But I couldn’t eat. I didn’t understand what had happened other than that I had been expelled from school for no reason, which had caused my parents to become very sad rather than angry with me. Finally, my mother sat down with a cup of tea and explained.

“Liebchen, you cannot go back to school for now. It is not your fault. It is all the troubles that we are having. It is for your own safety. Until then your father and I will arrange for you to be tutored at home.”

Up until this moment I had not realised my fate. In a matter of a few hours I had lost my friends, my daily activities and classes. I was no longer wanted. The suddenness of it filled me with a loneliness that I had never experienced before, and I burst out crying. I felt my mother’s arms embrace me and she started rocking back and forth, all the while making soothing sounds.

“Can I still go over to Anna’s?”

I would dearly miss my school friends, the classes, the activities, but most important was my dear friend Anna Jodl. We walked to school together, sat next to each other in class and walked back to Nürnberger Straße where we lived. We even stopped by my father’s shop on the way

where we always got candy, a piece of chocolate or even a pastry.

My mother hesitated for a moment and then nodded with a tight smile.

I didn’t want to ask about the troubles. I had been hearing about them for a while now, and whatever they were, I couldn’t understand anyway.

A week later a large woman with tight black curls, a wide, pasty face and a loud voice arrived early in the morning after Father had gone to work. She introduced herself as Frau Sundmacher, my tutor. She told us that the school had given her the curriculum and that she could teach me as if I were in class.

Winter had come early and it was already freezing outside. I missed not walking in the snow with Anna, however being tutored at home, even though I didn’t like Frau Sundmacher, made me feel like I still belonged. The weeks passed without the troubles getting any more troublesome.

In the afternoon, after I finished my homework, I would visit Anna or she would come over and we would play together. Other times, my other friends from school would come over. Curiously, when they did, we would have to play at Anna’s. The troubles prevented them from playing in our home.

But then in February the worries grew; the troubles became incidents, and Helga arrived.

During one of those late nights of hushed conversations my mother started to sob. The radio was on, but it was turned down low. Despite that, I could hear a man speaking angrily, threateningly. Every so often he would stop and the crowd would roar, “Seig Heil” or “Heil Hitler”. I had heard Hitler before. Is this the troubles? Why is Heil Hitler preventing me from going to school or having friends over other than Anna? That night after the radio broadcast my parents added new words to the string that I had heard before: Juden, Gestapo, SS, vandals.

In the morning Father left for the shop, and when I was seated with Mother I asked her if she was feeling well.

She nodded and, with heaviness in her voice, added, “There was an incident at the shop.”

I wasn’t aware of anything different because I had not been by my father’s shop: I had not walked by since I was expelled from school. I waited for her to say more but she proceeded to quietly put the dishes away and clear the table so that Frau Sundmacher could have her cup of tea and start my lessons.

I couldn’t wait for the afternoon so that I could ask Anna what the incident was; I knew that she would tell me. After all, she still walked past the shop every day from school.

In the afternoon, as Frau Sundmacher’s considerable backside waddled down the stoop, I listened intently for Anna’s voice. She soon rounded the corner and bounded up the steps. This time she had another girl in tow, short and plump with dark wavy hair and brown eyes. Her face was freckled and her eyes had a malicious glint to them. Unlike Anna’s cheery smile, her friend’s mouth was turned down in a snarl, like a stray dog’s. Anna and I looked very similar, like sisters: me with blonde hair and green eyes, Anna with blue eyes.

“Ruth, Helga is staying with us. She is from Munich. Helga, say hello to Ruth. She is my dearest friend.”

The girl hesitated for a second, then reached out her hand to shake mine. Her hand had a cold, clammy feel, like a dead fish.

“Is she sitting next to you at school?” I asked.

“No. She is just visiting for a few weeks.”

I was relieved and my heart swelled with love for Anna.

“Why aren’t you in school? Are you sick?” Helga stood resolutely on the landing and stared at me reproachfully.

I shrugged. “It is all these troubles we are having.”

Helga pointed at my chest. “In that case, why aren’t you wearing a yellow star?”

My mother appeared at the doorway to our building, greeted Anna and Helga warmly and invited us in. As soon as we were seated around the dining-room table Helga started looking suspiciously around the room.

“Why don’t you have a picture of Adolf Hitler on the wall?”

“We don’t have a picture of Hitler on the wall either. Papa says he is a mad fool who should go back to selling postcards,” Anna answered for me gleefully.

As soon as my mother placed biscuits and drinks on the table, Helga scowled in disgust.

“We shouldn’t eat Jewish food; it is poison to German children.”

“Well, in that case my whole family should be dead. We have been buying food from Herr Lipschutz for as long as I can remember.” Anna dove eagerly for the biscuits and drank to the bottom of her glass, smacking her lips in satisfaction. “See?” She looked triumphantly at Helga.

In the end they left. I sorely missed not having Anna to myself for the whole afternoon, but I was glad to be rid of the horrible Helga.

Notwithstanding Anna’s friendship, I was left with a feeling of disquietude. I was being shielded from troubles that now affected girls my own age. Not just the expulsion from school: I was no longer separated, but segregated - I wasn’t allowed to stray too far from our house; I couldn’t have any friends over other than Anna; I was asked why I didn’t wear a yellow star, why we didn’t have a picture of Hitler on our wall; and Helga would not eat our food because we poisoned German children.

I am a German child.

This growing sense of isolation and silence that engulfed my life became claustrophobic. I wanted to lash out and protest at my unjust fate, but did not want to upset my parents any more than they were already.

But silence had its own deadly clamour that shattered our world soon after Helga’s visit.

BELLEVUE HILL,

EASTERN SUBURBS, SYDNEY

AUTUMN 1986

Ernie Weissman died this year. He didn’t die well, as they say, somewhat paradoxically, as death is never good; suffering through a long and protracted illness which led him in stages from a graceful retirement in reasonable health at home to confinement in an old-age home battling a blood disorder, and then to a private hospital where he deteriorated into dementia and finally death.

When he finally succumbed, his wife of fifty years, Ruth, was relieved. Despite her unwavering love and devotion to Ernie through all the years, and bearing him one son, it had become impossible for her to see any pleasure in his life in the latter years; it had turned into one prolonged routine of ministering to an ever-increasing state of disorientation and debilitating illness, such that, by the end, it was impossible to identify the Ernie she loved in the hollow and frightened mask that stared at her, unrecognising, from the pillow in his hospital bed. It was more of a wraith that clung to the last pulse in an emaciated body refusing to give up the ghost.

In the first few months following his death Ruth found her widowed state impossible to fathom. For as long as she could remember her life had been occupied together with Ernie; whether it was the weekly trip to the Northern Beaches to spend the Sunday with their son’s family, the daily domestics, movies, theatre, concerts, overseas and local holidays, or attending Schule during the high holidays. Ernie was not just her partner of half a century but also her closest confidant and friend.

Even as his life deteriorated, withdrawing from those activities that described their lives, her routines nonetheless focused on maintaining a semblance of a life with Ernie by developing new routines that encompassed his existence: cooking meals that she knew he loved and taking them up every morning to the old-age home, and then to the hospital. Sitting silently by his bedside, as he lay there, unconscious to the world, holding his withering hand firmly, believing that he knew it was she, even though his eyes portrayed no recognition. Reading him the Saturday paper that they used to enjoy together; shaving him and changing his pyjamas when she thought he appeared bedraggled. In the last days, when death was all but inevitable, she never left his side, except to use the bathroom or grab a quick meal in one of the nearby cafés.

On the 14th April, an overcast Tuesday, she returned from the hospital café to find the nurse pulling up the sheet over what remained of the person who had been Ruth’s inseparable companion. At first she was disbelieving, even though at a deeper level she knew

this to be inevitable, her knees wobbling as she grasped for the nearest chair and fell into it, unable to look up at the bed that now contained no more than a sheathed corpse.

With a slight shudder she started to weep silently, more out of a sense of relief that Ernie no longer had to endure the illness that had robbed him of his dignity and rendered him helpless. He could rest and be no more the curse of all those humiliating whispers of well-meaning acquaintances and friends.

After a while, left alone in the grey, grim room, she rose up, lifted the sheet off his head, kissed warmly his shuttered face, replaced the sheet and left.

Back at home, her life was suddenly empty. It had been a life with Ernie. It had been a life lived in the care of Ernie. And now it was just her.

After the service, the funeral and kind words dissipated she was left alone, as she had been the last few years. Except her life now had no purpose. She continually turned down invitations to go out, to play bridge, to go to the movies, to the theatre, to stay with friends. She even refused to travel with her son to his home and spend time with his family.

She felt totally empty. Staring blankly at the TV at night. Eating tastelessly through her meals. Changing into her going-out clothes, even though she could have remained in her housedress; she never left the front door. The groceries were delivered courtesy of her daughter-in-law; the bills attended to by her son.

THE MADNESS LOCKER

THE MADNESS LOCKER