- Home

- EDDIE RUSSELL

THE MADNESS LOCKER Page 3

THE MADNESS LOCKER Read online

Page 3

I remember as a youngster running with my mother to the Benz factory gates to await my father’s pay packet and then hurrying to the shops before the money diminished to half its value. It was like carrying water in a leaking pail. What kept our heads above water was my father not losing his job and Grandma’s house. Take away either or both and it could be us on the street.

The carriage is swaying gently from side to side as we pull out from Leipzig on the way to Bremen. The thoughts swirl in my head as I stare out the window. I wonder at my decision to leave Germany. Am I abandoning my country because it is failing? Have I lost hope of a resurrection? Or is it my sense of unease about Hitler and the Nazis? I know I want to go somewhere where my remaining years of study will not be racked by worry as my last four years at Leipzig have been.

BELLEVUE HILL,

EASTERN SUBURBS, SYDNEY

AUTUMN 1986

“So you can’t sleep?” Sam watched as Ruth went about setting out cups and saucers in the kitchen and turning the kettle on. When Ernie was alive he would unhesitatingly walk into the kitchen and stand close by Ruth, chatting. But now he knew that the proximity would make her feel uncomfortable and him awkward.

With the clatter and the noise from the electric kettle she couldn’t hear him. He didn’t mind. He rose from the couch and started wandering around the comfortable living room. Except that now, with Ernie’s death, it seemed different: suggestive of possibilities. He could easily see himself in these familiar surroundings. And why not, he thought to himself? After all, he still felt virile. And Ruth, well, Ruth was what Ruth had always been: very attractive. In fact, he would go so far as to say sexy. It didn’t matter that she was just shy of sixty. It was all relative.

When he was in his thirties, a woman of early to mid twenties was attractive and desirable. Now he was in his early seventies, so a very trim, healthy woman with pearl-white skin, green eyes and a head of full, flowing hair was very desirable. Naturally he wondered about the even colour of her hair. But then what did it matter - women needed more cosmetics to safeguard their vanity than men. And besides which, he wouldn’t be lusting after a woman who appeared frumpy in a housecoat with straggly grey hair. At any age, one needed to look after oneself.

Appearance. Yes, that. Appearance and intimacy. Such odd bedfellows. And here, well, if there were possibilities, the two would remain irreconcilable. Nevertheless, there was always the foolishness of the phrase ‘Love conquers all’, but Sam was too level-headed to fall for such prattle.

“Sam!” Ruth was standing by the coffee table with the cups laid out, and about to pour the coffee. He didn’t hear her come back into the living room.

“I am sorry, I was looking at the photos and remembering what a wonderful friendship I had with Ernie.” Sam moved away from the mantelpiece and sat down opposite where Ruth was standing.

She knew he meant that kindly, but somehow, like everything else about Sam Steimatzky, it sounded false. Like he was expressing a sentiment that was rehearsed or scripted and expected of him. Always correct, always infinitely polite. German. Very German.

She ignored his remark and proceeded to pour steaming coffee into the two cups. Without asking, she placed two sugar cubes in his and added a dash of milk. She had prepared his coffee enough times.

Reaching for the edge of the saucer, he placed it next to him on the side table and settled back into the settee. He waited for Ruth to get comfortable before he resumed the conversation.

“I was saying before when you were in the kitchen - you have trouble sleeping?” he enquired diligently.

“Sam, I know that you told us before,” she said, as though Ernie was in the room, “but where were you during the war?” If she was going to befriend this man that Ernie had sent along, then she needed to stop feeling awkward and suspicious around him. Either that, or Ernie would need to send another emissary to keep her company and stay her hand from death.

If Sam was rattled by the question and the obvious change in the conversation, he didn’t appear so. Pausing as if to collect his thoughts, he sipped at the warm coffee, set it down, and looked up directly at Ruth. “Well, that would depend what part of the war.”

“Well, let’s say 1943 to 1945, the final years. When it became obvious that Germany was starting to lose. Where were you during that time?” Her face remained intent and resolute, as though whatever answer he gave would require further scrutiny.

“Well, I have to say that I am rather ashamed to admit I was not doing anything heroic. I had managed to escape to Switzerland. I arrived in Zurich in the middle of 1943 and looked up an aunt on my mother’s side. She was extremely pleased to see me, so I stayed with her.” A cleanly bandaged answer. Nothing messy and disorderly, like an archetypal Jewish refugee story. Mayhem; capture; escape; betrayal; another capture; another escape, this time from certain execution; nights sleeping in woods, subsisting on scraps; and then by some miracle crossing over to the Russian side. Parents? Dead. Relatives? Mostly dead, or scattered beyond reach. Siblings? Dead.

Ruth had to admit that Sam’s sterile answer spoke of someone who was uncomfortable with the war, got into a Benz sports car, drove across to Zurich and whiled away the time between cafés and trips to the Alps. She certainly did not know anyone Jewish who had had such a comfortable and carefree exit from Germany across to Zurich and then waited out the war in a relative’s apartment.

“How did you manage to get out of Germany?” Her eyes narrowed, watching for any discomfort on Sam’s face. If Ernie were alive he would steer the conversation away from a topic that he knew Sam found awkward at best and difficult at worst.

“Ah, that would take a long time to tell, and involved quite a bit of subterfuge. Maybe we can defer that story to another time, when you are not feeling tired. And we are just having a pleasant cup of coffee.” As always, the neat answer swaddled in comfortable and plausible excuses.

“Yes, I would be very curious to hear how you managed to get out.” Ruth reached for the plate in the middle of the coffee table and slid it over to where Sam was sitting, offering him bagels with various toppings as if to suggest that time was not rushing and she was not tired.

“Ah, bagels. Emma used to get them with salmon and herring from Glickstein’s. Do you shop there too?”

Ruth didn’t doubt that Sam’s deceased wife had in fact shopped there - but it was the emphasis he placed on the Jewish deli and slathering on the salmon and herring that felt like he was trying too hard. Then again, maybe seeing the bagels had reminded him of his wife. Either way it failed to narrow the gap between them, which in times past Ernie had bridged. Her doubts notwithstanding, it didn’t necessarily make Sam a Nazi impostor, as she had always suggested to Ernie. There were many shades of grey in between.

The obvious question was why would he masquerade as a German Jewish refugee? She wouldn’t care if he were a German Gentile, as long as he had no past links to the atrocities of World War II. After all, she knew better than anyone that not all Germans were Nazis; otherwise she would not be here.

Again Ruth chose to ignore his question and, without appearing to press him on his actual escape from Germany, decided to get at least a feeling of the truth from a different angle. “Did Ernie ever discuss with you how he escaped from Germany?”

Now Sam seemed to be willing to return and participate in the conversation. “No, actually he did not. Not in so many words. I wouldn’t mind hearing that.”

Anything to digress from your own history, Ruth thought cynically to herself.

“Well, you know that he was taken by a transport from Bremen to a camp?” She deliberately let her eyes narrow, laser like, to see if the mention of a camp would rattle him.

Sam, at least for a second, appeared to lose his composure. He narrowly avoided spilling coffee on himself as his hand jerked the cup back into the saucer. “Yes. Yes, he did mention that.” All of a sudden his voice took on a raspy undertone, as if he were speaking out of fear or guilt.

<

br /> “Well, he had trained as a doctor, so that was a very valuable skill both for the Germans and the Jewish and other prisoners in the camp. So his life was spared. He also had easier access to move around. Because he was German and a doctor, as the war got worse for the Nazis, he was relocated from the camp, I guess they figured that the prisoners could be spared medical treatment, and was moved to the Eastern Front. I believe he ended up close to St Petersburg. As luck would have it, the Russians captured him. He was at first treated as a prisoner of war, but when they realised he was a doctor and a Jew they released him and put him into service. With the fall of Germany he returned to Bremen. But there was nothing there to return to. The family home was rubble, bombed by the Allies. All his immediate family were either dead or lost, God only knows where. So he left.”

“Did he come straight to Sydney?”

“Oh no. He took up the cause of medicine as a way to heal himself and went off to become a doctor in Africa. He ended up in Uganda, of all places.”

“Yes, that part he mentioned. But I wasn’t sure if he travelled there before or after he came to Australia.”

They were digressing, as uplifting as it was to recollect Ernie’s life. But Ernie was dead, and that line of conversation wasn’t leading anywhere useful. The fact was that Sam was alive, but he was also cloaked in a potentially questionable past. At some visceral level Ruth wanted to let her emotions bypass that uncomfortable suspicion; to dive in and figure out how to navigate the currents later. But that was just it: that sort of strategy could either set you on an adventure or get you drowned. In another time, at the prime of life, she would have let herself go. But now, with life on the wane, risk was not the course to steer her through; caution was. But how much caution, and to what level? At some point you need to let yourself trust someone or not. She was never going to get all her questions answered to perfection. Some things remained murky, cloaked in the mishaps of youth. Forgive and forget, as it were. And perhaps that was it: she was prepared to reach that crossroads, to forgive and forget, except she did not want to do it blindly. In effect, forgive and forget, knowing what she was forgiving.

With a brazenness that she would later recall with some misgiving, she lunged forward. But she was tired from a harrowing night of dark thoughts and hopeless choices. And maybe just a little too old to be playing these games that were more the province of teenagers than people their age.

“Listen, Sam, I would like to be perfectly candid with you if I may? I am enjoying this conversation that we are having, and I am also grateful that you came to enquire as to my well-being. But you are not here just to check on my health. There is a more - how shall I put it? - a more personal motive. No, no, that’s OK” - Sam edged forward in his seat, about to protest his innocence at this assault on his intentions - “you are a man, a very attractive man. You were a friend of my husband’s. Ernie is dead, and you figure you can strike up a friendship with me. See where it leads. And that’s fine. But men, they tend to be less suspicious, generally, than women. Ernie liked you and he chose to ignore a few inconsistencies, for want of a better word, in your life story. But if you want to come into my life and become my friend, then that is a risk I am willing to take - to a point. Friendship is like that. But there are some things that I must know, and unless I get some comforting answers I will have to risk not having your friendship, if that makes sense.”

For a stark moment her voice and the words that she had spoken reverberated in the room. And then the room fell into an awkward silence. She didn’t know whether it was what she said that shocked him or her level of candour. Either way, he sat there, frozen in the chair, cup and saucer suspended in mid-air. Gradually, he thawed. His skin grew taut, either in anger or in offence at her suspicions. The few lines that marked his face grew deeper until they formed clear ridges on either side. Slowly, ever so cautiously, he edged the cup and saucer over to the table; patted both sides of his ash blond hair that seemed to glisten with perspiration.

His voice, when he spoke, was a mix of indignation and hurt. “Well. I came to see if you were - how shall I put it? - sleepless. For a number of nights - at least since Ernie’s funeral - I have heard the TV or radio the whole night and into the early morning. I did not want to intrude. You and I have always been polite to each other. Never friends. Just polite. Hello. Goodbye. So I figure I won’t intrude. Then I think, well, maybe I should have a look, because you are not leaving the house. It is time that, for my friend’s sake, I check on your well-being, as you say. You have reason to be sleepless. Maybe you find yourself lost. I don’t know. I came to see if I can help.” Sam rose from the couch and stepped over to the window. Drawing the blind back, he looked out to the valley, which was now glistening with the early-dawn drizzle.

Speaking more pensively now than in indignation, he looked back at Ruth, who appeared to be rapt with attention, perhaps hoping to hear that what he was about to say would allay her suspicions.

“You think you are so clever. Trying to quiz me on what happened in the war. Where was I? How did I escape? Where did I serve? Maybe I’ll make a mistake and slip up, as they say, reveal something incriminating. And then you can jump up and say, ‘There - I knew it. You are a Nazi!’ You think I don’t know this? Ernie did not choose to ignore, he just chose to accept that maybe friendship is at times not knowing everything. Men are better at that. Less gossip. Huh? If you are so clever, why didn’t you think to ask the obvious question?”

“What? What question did I not ask?”

“If you are not sleeping, how do I know that you are not sleeping?”

With that he walked over to the door, and at the last moment turned back. “Ruth, you should think to yourself that maybe you are not the only one that cannot sleep at night. I have not slept a full night since, well, for as long as I can remember. Even when Emma was alive.”

With that he drew the door back, walked out into the grey morning light and slowly closed it behind him.

RACKELSWEG, BREMEN

AUTUMN 1934

The train pulled in at Bremen at just past noon. No one is waiting. I didn’t tell anyone I was coming.

Our house is on Rackelsweg. A quaint little street surrounded by ordinary trees and shrubbery, a short distance from where I disembark. I decide to walk a little way now that the weather is not inclement. If there is abject poverty and irredeemable desperation I see it less than in the cities I passed on the way. Unemployment is regionally high and young people, particularly graduate students, represent most of the unemployed: sixty per cent of the total as opposed to thirty-four per cent for white and blue collars.

No one bothers me as I walk. If there is begging it is probably confined to the higher-density areas: more people to feed the multitude of hungry hands.

After nearly an hour of walking unhurriedly I finally turn into our street. It is quiet and empty, as I always remember it. The gardens appear well tended and the elm trees provide shelter for the homes lingering in the noonday sun. There is no sign of the misery that has been racking Germany for the last three years. If people are unemployed and on the verge of losing their homes, no one is saying, but there was a suicide a year ago: a sales manager who lost his job and could no longer support his family.

Standing on the corner, I can see our home. It stands as it always has, no different than when I left and the few times that I came back on holidays. It is my childhood home. I want to remember it always as a happy place, despite the desperation of 1923 and the turmoil of now. In Holland I will be shielded; I will be protected. At least that is what I believe. And maybe when I get there I will learn something new about my own psyche: that I cannot be a German in exile. It is like the maudlin maxim, ‘Home is where the heart is.’

But that’s just it - where is home, when you lose it?

Above the gardenias I see my mother’s head bobbing as she clips a wayward branch here, a wilting flower there. She thinks she sees a figure in the distance, pauses for a minute, squints,

doesn’t recognise me, then continues pruning. The garden is her passion. The home is her love.

I take a few more tentative steps and walk along the hedge. My mother’s head bobs up again.

“Juhu, Freddie!” she cries from behind the bushes. She drops the secateurs and rushes to the gate. It swings open and she is out on the pavement, embracing me. “Why didn’t you tell us that you were coming back? Father would have borrowed a car and picked you up.” She is already reaching for my rucksack.

“I wanted to surprise you.”

“Well, you certainly have. Father and Brigitte will be delighted to see you.”

We are walking along the flagstone path to the front door. I am following Mother, lugging my bag while she fumbles with my unwieldy rucksack. Soon we are indoors, the familiar smells and sights of home replenishing my soul beset by uncertainty. I feel a sense of hope again, but I know that it is transient. You can only be a child at home at one time in your life. You can always feel like a child at home, but at present I am an adult with my future swinging precariously between wanting to stay and needing to leave.

I know that once I tell my family about my plans to leave Germany they will be greatly saddened and dismayed. The long-term plan was for me to complete my medical studies and become a doctor in Bremen. They would probably even be willing to accept that I might practise in another town or city so long as it is in Germany. But to go abroad is not something that they have even contemplated. Neither did I until Hitler came to power.

To explain my disenchantment with Hitler would reveal nothing more than the general portent of fear and terror that is sweeping across Germany like a toxic cloud. We lived with the anxiety and fear of economic chaos and civil anarchy under the Weimar; now we are being ushered into an era of terror and brutality under Hitler. We have traded one horrible state of affairs for another.

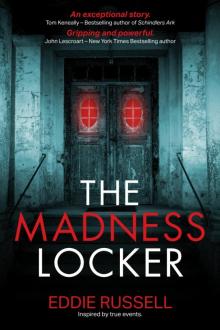

THE MADNESS LOCKER

THE MADNESS LOCKER