- Home

- EDDIE RUSSELL

THE MADNESS LOCKER Page 4

THE MADNESS LOCKER Read online

Page 4

But although my parents are well-educated, middle-class people they choose to remain politically blind, abiding by the law and order of the day regardless of its colour and creed. Somehow I need to reduce my misgivings and unease into a simple construct that they can assimilate and understand, not begrudging me my desire to leave. But how? This perplexes me, and I will cogitate on it until I find the compelling narrative and present my case. It is not that I have to persuade them of the justification of my aims, but that I need to silence my guilt over leaving them behind.

My mother is pottering around the kitchen, putting on pastries and a hot drink so that we can sit and talk about Leipzig - similar to when I was home last year.

“So you have graduated?” She pats my hand proudly.

“Yes.”

“So can we call you Herr Doktor now?”

I am aiming to strike a fair balance: not wanting to utterly shutter their illusion, but at the same time not set unrealistic expectations.

“I still have to complete my thesis,” I explain calmly, sensing that the process of earning the title is likely seen by her as mere academic bureaucracy. But at this moment I see an opportunity for me to explain why I have to go abroad.

Her face sours slightly. I believe that the burden of incurring loans for my education over four years has been more than enough hardship for my parents. Added to the upheavals of the Weimar Republic and the crash, which lost them their savings.

“I will be able to work and pay my own way, though, so you and Father need not worry.”

She is not easily placated, she averts her gaze sideways towards the window, pausing to let the light of reality seep in.

“What is the matter? Is there something wrong with Father?”

“No. It is not that. But you know, he has been working very hard, taking extra hours and shifts where he can to help support you. I was hoping you could open up a clinic and work as a doctor right away so that he can cut back.”

The guilt knife has plunged into my conscience already, and I haven’t even brought up the subject of my leaving Germany. I am beginning to wonder if she means cutting back to normal hours or semi-retiring, which he can do at fifty-five. But I don’t push the question; instead I try a different tack.

“I understand. And I would be willing to help, but I am not fully qualified to practise yet. But if Father does not need to support me any longer, won’t he be able to cut back anyway?”

“Have a slice of strudel, I know it’s your favourite.”

To placate my mother I pick up a piece and munch without too much gusto. I stay silent to get the full measure of where she is headed.

“Good, huh?”

I nod my head.

“Part of the reason that your father is working hard is also to rebuild our savings. With Hitler in charge the currency is stabilising and the economy is improving. We may be able to accumulate enough to retire.”

I was half right. It is not just semi, but full retirement. Not an uncharitable thought under the circumstances. The Weimar Republic and the crash of 1929 have plunged them into a financial hole and they are desperately trying to dig themselves out with whatever shovel they can get: Father working extra shifts; the expectation that I will work as a doctor to help pay off the loans; supplementing their income; maybe even Brigitte marrying someone wealthy. Had the prosperity of the 1923-1929 continued uninterrupted, being the parsimonious type, they would have had a sizeable nest egg by now in addition to Grandma’s house. In their mid fifties they would have been able to retire comfortably. As things stand at the moment, Father will have to work at least another five years until he is sixty, on top of which they need to start recalling favours and getting assistance from the only source they are not embarrassed to ask, both of which point to me.

I refrain from totally disillusioning my mother, but explain my predicament - “I won’t be able to get my licence to practise without specialisation” - implying that their four years’ investment in Leipzig will be wasted. If there is anything my parents abhor it is waste.

She nods her head, beginning to understand my situation. “Why don’t we wait until your father comes home and then we can discuss this tomorrow when we are all fresh? He does not work on Fridays - he works the Saturday shift, gets better money.”

I agree. I tell my mother that I need to rest a little after my trip and go to my room.

In Leipzig I imagined that all was well at home. I never asked and they never complained. They suffered the burden of my board and tuition quietly, stretching their endurance to the limit. The limit is now. They never expected to hear that I will be taking longer to start practising. That’s beyond what they can endure.

If I leave to go to Holland they will see it not only as a betrayal but as a desertion. The only way that I can see to persuade them that it is a good move is to not discuss Hitler or the Nazis and my misgivings, but the shorter path to my practising.

I am lying back on my bed, the same one that I lay on as a teenager dreaming of leaving home to study. I left with the sense that home was the bulwark of my being. It took just four years away for me to realise that the foundation on which I was relying is fragile and cracking at the seams. I don’t begrudge my parents their vulnerabilities, I just never anticipated the role reversal to arrive so early in my adulthood. I expected them to grow old and be grandparents before they came to rely on me for help.

But the devastation of the 1929 crash and the Weimar’s incompetence brought the clock forward. What if Hitler can revitalise the economy and stabilise the currency; might that slow things down again? My father could work normal hours; his pay packet restored to what it was before it was sheared in half. Maybe then I will not need to shoulder the responsibility of repaying my parents the debt before I have even become a doctor. I need to be the child just a little longer. In some tangential way Hitler is a saviour to us too. It doesn’t ease my conscience regarding his aims and ambitions, and certainly not regarding his methods, but it does allow me to find benefit even in a flawed messiah. It is the bedrock of comprises: we accept certain things half-heartedly because they serve our purpose too. The Weimar and the crash brought us Hitler.

I feel better about being back. Sitting in the dining room being plied with chocolate cake I felt like I was choking on a bribe.

I look at my watch. It’s getting late in the afternoon. I wonder where Brigitte is? I never thought to ask. She is my younger sister and we have always had a strong bond. I would like to air my thoughts with her before discussing them with the whole family. Mother is prejudiced, after all. Not that she loves Brigitte or me any less, but she and Father are getting old and they need their security. That is as plain as it gets; we are still young and time is on our side.

I am awake. I must have dozed off. I study my watch; the afternoon light from the window has turned to dusk. I turn on the night lamp: it’s six o’clock. The short nap on the train from Leipzig relaxed me. That and being in my old room and having graduated pre-med drained my body of any lingering anxiety. But just as soon as I relish the relief it is replaced by a sinking feeling in my stomach: I still have to confront my parents about my upcoming plans. Sooner rather than later we are going to have that conversation, and despite the sound rationale behind my reasons for leaving it will not be an easy discussion.

Father will most likely mirror my mother’s disappointment yet their stoic Teutonic attitude and ultimate desire to see me succeed will prevail and they will sit there and smile benignly and assure me that everything will be fine. But in another four years’ time when I return home from Holland I might discover that the their life has deteriorated further: my father aged faster than his years; the house fallen into disrepair and the only asset to sustain them in their old age, Grandma’s house, sold off so they can survive.

That is the lateral view, I remind myself, to alleviate my growing sense of anxiety. The wild card is Hitler. If he can restore Germany to the prosperity of the pre-crash years then th

ings will look up. I remember seeing him parading around in a Benz; that’s a good thing for Father’s plant. But then again, Hitler can afford a Benz - how many of us can afford one, is the key.

I hear voices downstairs: Father’s, then Brigitte’s and then Mother’s. All the family is home. I swing my feet over the side and then on second thought roll back onto the bed. Knowing the predicament that I face now, I shouldn’t have come back. I ought to have gone straight from Leipzig to Holland. They would have found out sooner or later and I would have made up some story as to why I was completing my medical training overseas. Now I am trapped by my guilt.

Footsteps come towards my room. They are soft and tentative.

Then a quiet whisper, Brigitte’s: “Freddie, are you awake?”

Her head is in the door and the night lamp is on; I can hardly pretend that I am not. She rushes in and hugs me.

“Oh, it’s so good to see you.”

“Sorry. I fell asleep. I didn’t think I was that tired.”

She sits on the edge of the bed. “Don’t worry, you were tired; who cares why? You are home now. Are you home for good? Father thinks that you are.”

I point to the door. She nods her head, walks over and shuts it.

“What’s going on? Did something happen in Leipzig?”

“No, no. Everything is fine. It’s just that they want me to start working as a doctor right away, even open up a medical clinic. But I am not there yet. I have a way to go.”

“Ouch.”

“Ouch, what?”

“Well, Father has been running around telling everyone that Dr Becker is coming home. He has even been making enquiries locally for your clinic.”

“Ouch!”

“Well, he will have to go back and tell everyone that he spoke too soon.” Brigitte shrugs nonchalantly.

I shake my head in bewilderment.

“So, there is something wrong.”

“Not quite wrong, but disappointing.”

“You’d better tell me so that I can soften the blow for them.”

“I am thinking of going overseas to complete my studies.”

“That is going to be a blow. May I ask the reason?”

“Reasons. I need to get away to get some perspective on what’s happening here.”

Brigitte points outside the door.

“No. Not home. Germany in general.”

“What? You are not persuaded by Dr Goebbels’ promises of a new era for Germany?” She smiles sardonically.

I shake my head and smirk but don’t say anything.

“Look, I got a teller’s job in Domshof. Deutsche Bank. Eight, nine months ago I wouldn’t have bothered trying.”

“Are you saying that things are improving?”

“The mood of the people is certainly improving.”

“Well, that is something for some people. Others are going to fare worse.”

“That’s always the way, regardless of who is in power. A lot of people did well under Weimar, before the crash, and others still lived in barns. We were fortunate. Father kept his job.”

“But they lost their savings.”

“They lost their savings. What can you do?” Brigitte says it more as an unavoidable consequence than as a question, shrugging her shoulders. “You said reasons, before.”

“Reasons?”

“You know, for leaving Germany.”

I nod my head. “And to get away from this.” This time I point towards the door.

“I know what you mean. Before I got a job they would set me up every week with horrible dates. Remember Ulrich Koertig, the one that used to work at the school with Mother?

“The caretaker?” I am dumbfounded. Brigitte can do better both socially and physically. Though I would describe her as more pleasant looking in a traditional sort of way, her fleshy features taking after mother’s, with light-blonde hair, green eyes and standing above average in height, I concur that Ulrich falls short in every way. I don’t say it and neither do I express the view that our parents must have been panicking with Brigitte still not spoken for and the economy floundering in even suggesting the caretaker.

“Yes, the one and the same. I don’t think that we could fit on the same bed together.” Brigitte and I burst out laughing. “I would be in the kitchen preparing meals all day, every day just to feed him. Anyway, now that I am working, they ask me about men at the bank. They are worried that I will become an old maid, like Auntie Agnethe.”

“I didn’t even think of that.”

“What, that I will become an old maid?” She slaps me playfully on the shoulder.

“No; that they will put the same kind of pressure on me. You know, to meet someone, settle down.”

“Maybe we should marry each other. We get along.”

We laugh again.

“Listen, why don’t you rest some more? If you want me to, I will tell them that you are tired and will sleep through to tomorrow. Don’t worry about them. All parents have expectations and children end up disappointing them.”

I start to feel better. Some of the load is easing off my shoulders.

“Tell them I will be out in a little while. I will have a shower, freshen up and then come out.”

“Good idea.” She kisses me in a sisterly manner and eases out the door.

Mother has prepared what would be a traditional holiday meal for this occasion. She is a wizard in the kitchen; I don’t even know how she got it all done in just the afternoon. By the time we get to the butterkuchen I can hardly fit in a single slice without loosening my belt a notch.

We have talked about Leipzig, Father’s work, Brigitte’s prospects socially and at work, Mother going back to working part time. The only thing we haven’t talked about is the subject on everyone’s mind: my future. But nobody wants to be the first one to raise it for fear of spoiling the mood.

Finally Brigitte broaches the subject in an ingenious subterfuge, taking the heat out of the topic. “Freddie has to go another year; specialisation. Overseas. To complete his degree.”

Father looks, flabbergasted, from Brigitte to me. “Is that so?”

I pause to collect my thoughts, trying to sound as convincing as possible. “All doctors are required to put in a year of internship abroad.”

“Africa?” Mother is looking worried.

I nod my head sagely. “Could be. But I chose something closer to home and safer: Holland.”

“Very good.” Father slaps his thigh.

Brigitte has saved me from having to disappoint them and turned a potentially unhappy reunion into a happy farewell.

“Where are you going in Holland?” Father turns to me with a beaming smile. He can now proudly tell people that his son the doctor is specialising overseas.

Fortunately I already have the name. “Universiteit Utrecht.”

“Utrecht! Your mother and I have been there. It’s a very beautiful old city and quite the university town. The good news is it’s only four hours by car from here. We can come visit you.”

They are both excited and ecstatic now. Strange thing is that Leipzig wasn’t that much further and they nary came the once. They probably see going to Utrecht as an overseas holiday; Leipzig is just another town in Germany.

The rest of the evening is spent making plans to visit me. They decide that they will do so over the Christmas break when Father and Brigitte can take time off from work.

By nightfall I sneak into Brigitte’s room and kiss her on the forehead. “I owe you.”

She chuckles, tucked in under her blanket. “That’s right, Herr Doktor, and don’t you forget it.”

I spend a month in Bremen. Father parades me around to his friends and colleagues as Herr Doktor and they all, to a person, bestow me the honour. I am extremely uncomfortable with this travesty, but the alternative would be devastating for my parents and their fragile middle-class egos. I sincerely hope that nobody asks me to do a house call. After four years of arduous study I am knowledgeable enough about h

uman biology to understand the physiology, but taking an instrument to a live person or prescribing medicine would unravel the lie and make a mockery of my parents. They would never live down the shame.

Happily, fate conspires with my half-lie and I am not asked to perform any parlour tricks. I am a half-doctor, if anyone cared to check.

At the beginning of autumn I repack my duffel bag and rucksack and make my way to the bus station. There are no trains to take me to the border with the Netherlands. Instead I take a bus to Nijmegen and then board a train from the border town to Utrecht.

UTRECHT

AUTUMN 1934

I disembark at Utrecht Centraal just before noon, a short two-hour trip from Nijmegen on the all-stations trains. Given my eventual impecunious station, and that I’ll need to find accommodation immediately and employment within a matter of weeks, I plan to do both at the university.

The attendant at the train station points me in the general direction and assures me that my destination is an easy thirty-minute stroll. But if I don’t feel like a brisk jaunt, I can walk to Steenweg, five minutes away, and from there any number of buses will take me right up to the university. I don’t mind walking all the way but am not certain of my whereabouts, and getting lost would leave me without student lodgings so I walk just as far as Steenweg.

On the train I tried to imagine what Utrecht would look like, drawing comparisons with Leipzig and even Bonn, which I have visited. But nothing prepares me for this medieval city with its maze of canals and split-level houses and warehouses. Whenever I think of canals Venice comes to mind, but Utrecht’s waterways are just as quaint and romantic as the Italian city’s, and though I’ve never visited Venice I imagine that it is culturally rich with museums, cathedrals, magnificent plazas and sculptures arrayed throughout the city. Utrecht is not dissimilar in many ways. It is known as a university town but not in the way that Leipzig is: overrun with students, clubs, bars and student housing; more like Oxford or Cambridge, criss-crossed with canals and beautiful architecture.

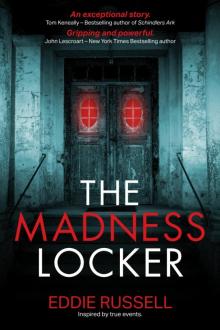

THE MADNESS LOCKER

THE MADNESS LOCKER