- Home

- EDDIE RUSSELL

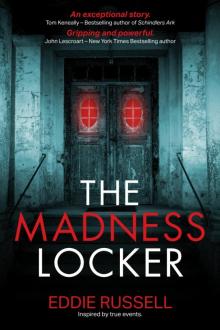

THE MADNESS LOCKER Page 5

THE MADNESS LOCKER Read online

Page 5

When I first thought of Utrecht, the fact that it had a prestigious teaching hospital and its proximity to Bremen were what first attracted me to it, notwithstanding its foreignness. But now I feel quite at home with the genteel nature of the town; the unhurried pace of the passers-by, the air of learning imbued in the historical richness of the place. I slow down and draw my breath in deeply; I have made the right choice.

On the way I am struck by the most obvious question that I am likely to be asked: Why are you not continuing your medical degree in Leipzig? There is little doubt in my mind that if a place is available at the faculty of medicine at Universiteit Utrecht, based on my pre-med grades, I will be admitted. But Utrecht is a foreign city and speaks a foreign language. It will take some effort on my part to acclimatise to the Dutch language so that I can follow the lectures and read the books. What academic reason do I have for undertaking such a venture? I can’t argue pedagogy or the course curriculum; I don’t know enough to draw a favourable comparison.

I arrive at Steenweg and board the bus. The trip only lasts a few minutes but, preoccupied as I am, I almost fail to notice the university campus looming up ahead of me and am alerted by the bus driver who announces the stop. I disembark, not having as yet formulated a plausible explanation as to my choice of Utrecht. It doesn’t have to be surreptitious or suspicious, but the cultural change and linguistic challenge invite curiosity and a persuasive answer will smooth the enrolment process.

I disembark at Servestraat with the university gate just ahead of me. As I start to make my way into the campus, I find my reason, walking past me: two obviously Jewish men dressed in black cassocks and hats, sporting scraggly beards. They resemble those vulgar caricatures that denigrate and accuse the Jews of being vile and devious moneylenders plotting to destroy Germany, courtesy of Der Stürmer - a virulent anti-Semitic tabloid - and Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister. I rebrand my mother, Marlis Becker (née Wolfssohn - the only other Jewish person I know besides Zeigler), as Jewish, so I am perforce half Jewish. I can’t make my father, Herman, Jewish with a surname like Becker. I am counting on the fact that Holland is traditionally racially tolerant as a rule, and in particular to Jewish people, who have a long and prosperous history in Amsterdam. The reason for my leaving Germany and wanting to study in Utrecht is now ironclad, easily justified.

I enter through the massive wrought-iron gates adorned with a crest inscribed in Latin and entwined with creeping vines through the bars. They are drawn back for another day of learning as students and faculty stream through. Just within the courtyard, a short distance from the gate, is the most famous landmark in the city, the Dom Tower. An inscription at the bottom identifies it as the highest church tower in the Netherlands, and that it was built between 1321 and 1382 as part of the Cathedral of St Martin.

I am impressed with the antiquity and architectural grandeur, but I am rather indifferent towards its religious significance. If I was devout anything I would be leaning towards the irreverence of Lutheranism, the religion of my birth, and not the obsequious reverence of Catholicism, of which this church is clearly part.

Aside that, and the other myriad reminders of Catholicism scattered throughout the city, which do not feel oppressive, I shrug it off, maintaining my initial impression of Utrecht, and continue towards the centre of the courtyard. A signpost is planted right in the middle with labelled arrows. I try to decipher in them ‘admissions’ or ‘new students’, but nothing close to German jumps out at me.

A young woman pushing a bicycle stops next to me. She asks me something in Dutch. I shrug my shoulders and shake my head. She then reverts to English. I answer hesitantly, “Sorry, I am German. My English is better than my Dutch, but not fluent either.”

To my surprise she answers back fluently in German: “That’s all right. I am quite comfortable speaking German. You looked lost, looking at the signpost.”

I can’t believe my good fortune. “Are you German?”

“Oh, not me, my mother. She is from Leipzig.”

“Leipzig? Really?”

“Why? Don’t tell me you come from Leipzig. That would be too much of a coincidence.”

I find myself too instantly captivated by her easy-going manner and the sparkle in her light green eyes to mind her forthrightness. “No, no. I am from Bremen. But I just finished four years of premed in Leipzig.”

“And?”

“And? And what?”

“Now you are in Utrecht to do your medical?”

“That’s right.”

“May I ask why Utrecht and not Leipzig, or even Münster? They are just as good if not better.”

I am furiously debating whether I should test out the lie that I just invented. I am inclined to do so given that, if it does not convince, there will be no penalty. But it is too soon in the conversation. “You are right, Leipzig and WWU are very good. It is personal.”

That whets her curiosity. I am flattered that she is interested.

“Personal? How personal? A girl? Or something other, confidential, none of my business?”

I smile bashfully. “No, not a girl. Who has time in pre-med?”

“Then...?”

I clam up.

“Sorry, here I am prying into your life and I don’t even know ... ” your name.”

I reach out my hand. “Friedrich Becker.”

“I am Emma. Emma van Bergen.”

Her hand feels warm and small in mine. I like the tenderness and vulnerability of her touch.

“So, Herr Becker, now that we know each other, why Utrecht?”

“Herr Becker is my father. I am Friedrich, and I will happily tell you except I need to get to admissions, enrol and find a place to live.”

“Well, young Becker, walk with me; I work in admissions and I can help you with accommodation. So this is your lucky day. So, why Utrecht?”

We walk away from the Dom Tower and head past a series of similar old-looking buildings with the words ‘faculty’ and ‘institute’ forming part of their names, but other than recognising that I can’t make out the actual disciplines. Medical school is going to be hard going here in Dutch Land.

“Utrecht is the nearest place I could find outside Germany where I think I can fit in and complete my degree.”

“Really? You can’t even read a signpost; how do you propose to get through medical school reading all those dense textbooks, never mind the lectures?”

“Well, OK. I need to enrol, find accommodation and brush up on my Dutch.”

“I think you need to do more than that. Regardless, why put yourself through all of that?”

“You are a curious type, aren’t you?”

“Curious and direct, but only when I like someone.”

I am flattered even more by her indirect compliment. I instantly know why I like this young woman: her directness and natural curiosity aside, which don’t sound crass or obtrusive coming from her, she is the exact opposite of what I dislike about German women; she is sprightly and easy-going. I catch myself jealously wondering if she already has a boyfriend, and yet I only met her a few minutes ago.

I am glad that I declined the invitation to go with Martin Keller to Bologna. It was tempting to have a friend in a foreign city facing nearly the same challenges as I am here: oppressive Catholicism, foreign language and culture. Yet intuitively Holland felt right just as Italy felt wrong.

We walk quietly for a minute or so and then Emma stops. “Would you like to have a drink before filling out forms?” She is pointing to a squat building to our left. It is more industrial and modern-looking than the surrounding stately institutions of learning.

I hesitate.

“I am here. So you can’t fill out forms and enrol without me.” She pulls her bicycle into a rack and leads me gently by the arm into the interior.

It is nearly lunchtime and the large hall is crowded with people. She points me to a table by the window that is not nearly as full, and we gravitate towards it.

“What can I get you?”

I am trying to come up with what I would eat if I were in Leipzig. I hadn’t thought of food yet, so I haven’t noticed what they eat in Utrecht. “Can you get a beer and a pretzel?” I smile sheepishly.

“Beer, yes. I am not sure about the pretzel.”

Emma wends her way dextrously through the crowd and I am left alone at the table with a group of noisy Dutch students: two males and two females. They eye me curiously and one of them leans over, rattling something in Dutch.

“Nein Dutch,” I attempt politely.

Another of the group stands up and salutes - “Heil Hitler!” - mimicking Der Führer by substituting two fingers in place of a toothbrush moustache. They all burst out laughing.

I ought to have expected this, but not on my first day and not in this casual setting. I turn away and look for Emma in the crowd. I can see her head at the counter.

The Dutch student who spoke to me first leans over and taps me on the shoulder. He attempts, in broken English, “Why you here in Utrecht?”

I turn to face him with a sullen stare. “Study.”

He stands up and mimics a chopping motion over his penis. “I am Jew.”

I get it. Circumcised. This is getting ugly. I fully expect it to end up in a brawl on account of their antipathy to Germany. Ironically I am here for exactly the same reason, but being taunted in this manner I can’t make that point. I smile benignly. What else can I do? I turn again to look in the direction of the counter. Thankfully Emma is heading back with two beers and, amazingly, two pretzel lookalikes.

She arrives at the table just as the second student, the one who imitated a Hitler salute, walks up to her and speaks aggressively in Dutch. She sets down the beers and pretzels and assumes a belligerent pose, firing back at him. An argument ensues, with the other three students at the table joining in. I am tempted to get up and stand by Emma but fear that my intervention will escalate this argument into a fist fight. So I remain seated, hoping that they do not get violent. I can’t see them attacking Emma; she is, after all, one of them. Thankfully the other students around us take cursory notice of the scene, engrossed in their noisy conversations.

Eventually the heated discussion loses steam and Emma sidles into the seat opposite me, shaking her head with dismay.

“Thank you for the beer and pretzel; how much do I owe you?” I can’t think of what else to say.

“My treat.”

We remain quiet.

“I am sorry to cause you this much trouble.”

“No. I apologise. Normally, people here are very friendly. I am not sure what happened.”

“Please do not feel that you have to apologise. I can understand their hostile feelings.”

“Can you? Because I can’t. They don’t even know you and are blaming you for what the Nazis are saying and doing.”

We drink our beers and eat the quasi-pretzels quietly, ignoring the hostile stares and muttering to our left. The alcohol helps to settle my nerves somewhat. As soon as we finish we don’t linger, but take our trash and leave the table. More taunts flare up behind us as we make our way out. Some of the words are deliberately uttered in English for my benefit.

But there’s nothing I can do about who I am or how I look: I stand close to two metres tall with a muscular build, thick blond hair, and what passes for a handsome Nordic-like face with light blue eyes and peach-coloured skin. I speak with a distinctly northern Germanic accent. I am the model Aryan, if one chooses to espouse the idiotic posters that the Nazis are putting up.

Ironically none of the party members that spout this drivel match their own embodiment of the perfect German. They are either mousy-looking, squat with dark hair, brown eyes and a scrawny body, or obese and ungainly, or half crippled and mentally feeble. So they laughably fail to live up to their own standards and resemble more the caricatures that they vilify.

But by creating this mythical German Zeus they indirectly place me in the line of fire, as though I am the ambassador for their crackpot politics. Which I am anything but - yet, now I have crossed the border to the Netherlands it lands me in hostile situations such as this one. I need to present myself in a better light and distance myself from Nazi Germany as much as I can.

“You are OK?” Emma is by my side, pushing her bicycle towards the administration building.

“Yes. Thank you for standing up for me. I don’t know what I would have done had I been alone.”

“Forget it.”

We reach an older but pedestrian-looking building on campus, not of the same standard as the stately cathedral and faculties that we passed previously. Emma parks her bicycle and leads me inside. She points me to a counter at the end of a large room, then goes through a door and comes out the other side facing me and picks up a stack of forms. There are several clerical people working at desks behind her.

“First you have to fill out this form. It is for foreign nationals such as yourself. For address, you can put down mine.”

I look at her hesitantly.

“I share a house not far from here with a couple. There’s a room for one more person. That could be yours if you want it?”

My sense of alienation has swung back to feeling at home. I nod eagerly and take the form. It’s in English, the lingua franca the world over. I fill in my particulars, leaving the address in Utrecht blank, and hand it back, together with my passport as proof of identification. I then fill out the enrolment for the medical degree that I will be undertaking and attach my certificate and transcript from Leipzig. There’s a question about my level of proficiency in Dutch. I leave that blank and hand it back to Emma too.

She fills out her address on the first form and, on the second, writes Passing for reading and writing comprehension in Dutch. I refrain from commenting due to the other people in the office behind her, but raise my eyebrows in surprise at that blatant fabrication. She stares back - “Trust me, you will be” - then clips the forms together along with my enrolment processing fee and passport.

She then pulls over a map of the campus and places it in front of me. “Why don’t you go over to the library and spend the afternoon there? Strangely, they have newspapers and magazines from Germany. I will collect you when I am done here. Where are your things?”

“At the train station.”

“OK. The library is here.” She points to a building two lanes over from where we are. “Try and stay out of trouble.”

“I will try.” I smile back.

“We will collect your things on the way home. Welcome to Utrecht.”

I am tempted to lean across the counter and give her a peck on the cheek, but doing so, even innocently, may cause problems for both of us given her position. Instead I nod gratefully and head towards the library.

I recognise the library by the wide portico with three columns arrayed on either side of the entrance. Between the columns are statues of classical scholars: Aristotle, Plato, Socrates, Pythagoras and Archimedes. Rising above them on the pediment is a large cross with a cursive Latin inscription that I don’t recognise.

Just as I start to mount the steps, the same group of students from the lunch hall accost me, blocking my ingress into the building. My first thought is that they are spoiling for a fight and now that Emma is not with me they have no reason to hold back. I come abreast of them, betraying no fear.

“So, Mr Aryan, where is friend?” It is the same student that gave me the Hitler salute.

I ignore the question and proceed to push my way to the wooden doorway. They shove me back.

I raise my hands. “Don’t push!”

“Or what?” This is the student that airily chopped his penis.

But there is no time to get into a fracas, for two campus officials rush up. They grab the two male students and push them up against the wall. A terse and loud dialogue ensues between them. There is some head-nodding, a cocky smile from the students and they are released to continue on their way.

T

he salute student turns to me as he is leaving. “Next time you no so lucky!”

I flick the backs of my fingers under my chin and proceed to walk into the library. The one girl from the earlier lunchroom encounter softens her hostile glare and actually gives me a mischievous smile. I can’t tell whether she is spiting me or in some bizarre way admiring me. I haven’t displayed any great courage other than being foolishly stubborn.

I am followed into the library by one of the campus officials. “Sorry for that.”

I nod. “Not to worry. Thank you.”

The library is a massive semicircular building rising up four storeys. Each storey is lined with books right the way around, stacked ten shelves high. The bottom level has rows of study carrels with a goose-necked lamp attached to each one.

I make my way to a wall rack lined with German magazines, select a few and find an empty carrel. Regardless of their underlying political or religious affiliation, they all contain articles on the Nazis and Adolf Hitler, with one particular magazine featuring him on the cover - a dark, brooding likeness, rather than the more common menacing look - with the caption Germany’s Saviour? I am relieved that the editor or publisher had the sense to add the question mark.

Among his followers, Hitler has assumed messianic status, the sort of fanatical fealty that suffocates those who do not support him. My parents are avowed law-abiding neutralists and, if Hitler’s machinations do not threaten my father’s livelihood or their money, they will remain safe. So the weight of my guilt lessens. I do not feel that I have abandoned them to a precarious state. I don’t know any people from the disenfranchised group, other than Johann Ziegler. I salve my conscience in the hope that the senior Ziegler’s academic status will protect his son and family from any misfortune.

I don’t bother with my magazine-reading any more; it just makes me feel more nauseous. My last full meal was mid morning when I stopped at Nijmegen to catch the train to Utrecht. The pretzel and beer helped tide me over, but I am looking forward to my first dinner with Emma.

THE MADNESS LOCKER

THE MADNESS LOCKER